|

***

ЛИТЕРАТУРА

Мои дополнения по теме. Сочетание [Solenopsis invicta + venom] упоминаются в 429 статьях, огненный муравей Solenopsis invicta - в 3016 статьях , venom - в 763 статьях , alkaloid - в 125 статьях, использованной здесь базы Formis-2003:

-

Adams, C. T. (1986). Agricultural and medical impact of the imported fire ants. Fire ants and leaf cutting ants: Biology and management. C. S. Lofgren and R. K. Vander Meer. Boulder, CO, Westview Press: 48-57.

-

Adams, C. T. and C. S. Lofgren (1981). "Red imported fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Frequency of sting attacks on residents of Sumter County, Georgia." J. Med. Entomol. 18: 378-82.

A survey of the human sting attack rate of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, on a sample population in Sumter Co., Georgia, USA, was conducted over a 12-month period. Seventy-seven families (310 individuals) initially participated in the program, but dropouts reduced the average study population to 272 individuals per month. A total of 213 sting attacks were recorded for 95 individuals. A majority (179) of these were recorded for rural residents. The greatest contact occurred from April to September, with the total sting attacks ranging from 18-35 per month. The highest sting attack rate occurred in persons under 20 years of age (50%); the number of stings declined with increased age. Females reported being stung at a slightly higher rate than males. Two individuals (1%) classified their sting reactions as severe, 26 (12%) as moderate, and 183 (87%) as mild.

-

Adams, C. T. and C. S. Lofgren (1982). "Incidence of stings or bites of the red imported fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and other arthropods among patients at Ft. Stewart, Georgia, USA." J. Med. Entomol. 19: 366-370.

Medical treatment for arthropod sting/bite attacks was requested at Ft. Stewart, Georgia, USA, by 329 persons during the period 1 April to 30 September 1979. A total of 370 visits, including 7 days hospitalization for 5 patients, was recorded for these patients. The red imported fire ant (RIFA) was responsible for 49% of the outpatient visits and 5 days of hospitalization. Attacks by unidentified arthropods were responsible for 26% of the visits. The remainder of the cases (ranging from 1 to 5% each) were attributed to wasps, bees, spiders, mosquitoes, ticks, chiggers and fleas. The predominant age category of military personnel, 18-44 years, accounted for 78% of the patients. Eight persons (5%) stung by RIFA exhibited symptoms of shock, and 11 (7%) developed secondary infections, most requiring multiple visits for treatment. Nine symptoms were identified for 278 patients, with edema (82%), urticaria (43%) and respiratory distress (5%) predominating. Other symptoms, which included nausea, vomiting, dizziness, numbness and blurred vision, occurred predominantly in patients under 25 years of age. Cost of treatment, based on data supplied by the Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Army, is discussed.

-

Adams, D. R., W. Carruthers, et al. (1989). "Synthesis of Trans-2,6-dialkylpiperidines by intramolecular amidomercuriation and by 1,3-cycloaddition of alkenes to 2-methyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyridine oxide." J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. I 1989: 1507-1514.

-

Allen, C. R., K. G. Rice, et al. (1997). "Effect of red imported fire ant envenomization on neonatal American alligators." J. Herpetol. 31: 318-321.

*[Pipping alligators, exposed to fire ant stings, showed decreased weight gain, for 3 weeks after exposure. 2 stung animals died; the second may not have been the result of stinging]

-

Alley, E. G. (1973). "The use of mirex in control of the imported fire ant." J. Environ. Qual. 2: 52-61.

-

Attygalle, A. B. and E. D. Morgan (1984). "Chemicals from the glands of ants." Chem. Soc. Rev. 13: 245-278.

-

Attygalle, A. B. and E. D. Morgan (1985). "Ant trail pheromones." Adv. Insect Physiol. 18: 1-30.

-

Blum, M. S. (1984). Poisonous ants and their venoms. Insect poisons, allergens, and other invertebrate venoms. A. T. Tu. New York. xv + 732 p., M. Dekker. 2: 225-242.

-

Blum, M. S. (1985). Alkaloidal ant venoms: chemistry and biological activities. Bioregulators for pest control. ACS Symposium Series No. 276. P. A. Hedin. Washington. xxi + 540 p., American Chemical Society: 393-408.

-

Blum, M. S., J. R. Walker, et al. (1958). "Chemical, insecticidal, and antibiotic properties of fire venom." Science 128: 306-307.

-

Blum, M. S. and H. R. Hermann (1978). Venoms and venom apparatuses of the Formicidae: Myrmeciinae, Ponerinae, Doylinae, Pseudomyrmecinae, Myrmicinae, and Formicinae. Handbuch der Experimentellen Pharmakologie. 48: 801-869.

-

Blum, M. S., H. M. Fales, Leadbetter, G., Leonhardt, B.A., Duffield, R.M. (1992). "A new dialkylpiperidine in the venom of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta." J. Nat. Toxins 1: 57-63.

*[trans-2-Methyl-6-((Z)-8-heptadecenyl)piperidine is the 3rd unsaturated analogue detected as a poison gland product. trans-2-Methyl-6-heptadecylpiperidine accompanies the unsaturated nitrogen heterocycle.]

-

Brand, J. M., M. S. Blum, et al. (1973). "Fire ant venoms: intraspecific and interspecific variation among castes and individuals." Toxicon 11: 325-331.

-

Brand, J. M., M. S. Blum, et al. (1972). "Fire ant venoms: Comparative analyses of alkaloidal components." Toxicon 10: 259-271.

-

Brand, J. M., M. S. Blum, et Ross H.H. (1973). "Biochemical evolution in fire ant venoms." Insect Biochem. 3: 45-51.

-

Brand, J. M. (1978). "Fire ant venom alkaloids: their contribution to chemosystematics and biochemical evolution." Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 6: 337-340.

[Solenopsis eduardi was synominzed with S. geminata by Trager 1991]

-

Buren, W. F. (1972). "Revisionary studies on the taxonomy of the imported fire ants." J. Georgia Entomol. Soc. 7: 1-26.

*[New data show that two species of imported fire ants (Solenopsis richteri Forel, S. invicta, n. sp.) occur in the United States. The two species originated from widely separated areas of South America. Hybridization has evidently not occurred in spite of their presence in adjacent areas in the United States. A taxonomic history of the Solenopsis saevissima complex is presented. S. richteri and S. quinquecuspis are resurrected from synonymy and elevated to species. S. invicta from Mato Grosso, Brazil, and the United States, and S. blumi from Uruguay are described as new.]

-

Callahan, P. S., M. S. Blum, et al. (1959). "Morphology and histology of the poison glands and sting of the imported fire ant (Solenopsis saevissima v. richteri Forel)." Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 52: 573-590.

-

Cavill, G. W. K. and P. L. Robertson (1965). "Ant venoms, attractants, and repellents." Science 149: 1337-1345.

-

Cole, L. K. (1974). Antifungal, insecticidal, and potential chemotherapeutic properties of ant venom alkaloids and ant alarm pheromones, Ph.D. dissert., University of Georgia, 172 p.

[Dissert. Abstr. Int. B 35: 3955] [Order # 75-02575]

-

Cruz Lopez, L., J. C. Rojas, Cruz Cordero, R. de la Morgan, E.D. (2001). "Behavioral and chemical analysis of venom gland secretion of queens of the ant Solenopsis geminata." J. Chem. Ecol. 27: 2437-2445.

Bioassays in a Y-tube olfactometer showed that workers of Solenopsis geminata (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) were attracted to venom gland extracts of queens. Gas chromatography coupled mass spectrometry analysis of individual glands of queens of S. geminata showed that the secretion is composed mainly of a large amount of 2-alkyl-6- methylpiperidine alkaloids and a tiny amount of a delta-lactone and a alpha-pyrone, which have been earlier identified as components of the queen attractant pheromone of Solenopsis invicta Buren. However, additional small amounts of a mixture of sesquiterpenes and pentadecene were found. The possible function of the sesquiterpenoid compounds is discussed.

-

Deslippe, R. J. and Y. J. Guo (2000). "Venom alkaloids of fire ants in relation to worker size and age." Toxicon 38: 223-232.

Piperidine alkaloids compose most of the venom of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, and we examined how six of these alkaloids varied across worker size and age. In a colony sampled intensively, the relative abundance of each alkaloid was highly correlated with worker size with one exception, and ratios of saturated to unsaturated alkaloids were positively correlated with worker size. Similarly, both the abundance and ratios of alkaloids differed significantly between the small and large workers sampled from colonies across Texas, USA. Young and old workers produced less venom than ants of intermediate age (3-7 weeks), and ratios of saturated to unsaturated alkaloids increased significantly with worker age. The differences in venom composition correspond to the size- and age-based functional roles of workers. (Abstract provided by author.)

-

Ginsburg, C. M. (1984). "Fire ant envenomation in children." Pediatrics 73: 689-692.

*[In Texas, generalized systemic reactions occur in about 2 or 3 children per 100,000.]

-

Hoffman, D. R. (1987). "Allergens in Hymenoptera venom XVII. Allergenic components of Solenopsis invicta (imported fire ant) venom." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 80: 300-306.

-

Hoffman, D. R. (1993). "Allergens in Hymenoptera venom 25. The amino acid sequences of antigen 5 molecules and the structural basis of antigenic cross-reactivity." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 92: 707-716.

-

Hoffman, D. R. (1993). "Allergens in Hymenoptera venom XXIV: the amino acid sequences of imported fire ant venom allergens Sol i II, Sol i III, and Sol i IV." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 91: 71-78.

*[Sequences said to be similar to those of Dolichovespula, and "support [the] concept that the ants are closely related to other social wasps".]

-

Hoffman, D. R. (1995). "Fire ant venom allergy." Allergy 50: 535-544.

-

Hoffman, D. R., D. E. Dove, et al. (1988). "Allergens in Hymenoptera venom XX. Isolation of four allergens from imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) venom." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 82: 818-827.

-

Hoffman, D. R., D. E. Dove, et al. (1988). "Isolation of allergens from imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) venom." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 81: 203.

-

Hoffman, D. R., D. E. Dove, et al. (1988). "Allergens in Hymenoptera venom XXI. Cross-reactivity and multiple reactivity between fire ant venom and bee and wasp venoms." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 82: 828-834.

-

Hoffman, D. R., M. W. Guralnick, et al. (1989). "Comparison of venom allergens from two species of imported fire ants. [Abstract]." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 83: 232.

-

Hoffman, D. R., R. S. Jacobson, et al. (1991). "Allergens in Hymenoptera venom XXIII. Venom content of imported fire ant whole body extracts." Ann. Allergy 66: 29-31.

A two-site immunoassay using monoclonal antibodies has been developed to measure the imported fire ant venom allergen Sol i III. The assay is specific for Solenopsis invicta venom, since one of the monoclonal antibodies does not react with Sol r III. A commercial imported fire ant whole body extract, known from RAST and skin test data to be potent, was found to contain 10.3 ug of Sol i III per milliliter. This was comparable to the content of an extract freshly prepared in our laboratory. The immunoassay detected Sol i III in an extract of fire ant abdomens, but not in head and thorax extract. The amount of imported fire ant venom in a potent whole body extract appears to be sufficient to provide possible protection for patients receiving it as immunotherapy, although this can only be verified by controlled clinical trials with intentional sting challenges.

-

Hoffman, D. R., A. M. Smith, et al. (1990). "Allergens in Hymenoptera venom. XXII. Comparison of venoms from two species of imported fire ants, Solenopsis invicta and richteri." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 85: 988-996.

-

Hoffman, D. R. (1995). "Fire ant venom allergy." Allergy 50: 535-544.

-

Jones, T. H., M. S. Blum, et al. (1982). "Ant venom alkaloids from Solenopsis and Monomorium species. Recent developments." Tetrahedron 38: 1949-1958.

The chemistry and biology of the ant venom alkaloids from the genera Solenopsis and Monomorium are briefly reviewed. The usual 2,6-dialkylpiperidines found in four as, yet unstudied species of Solenopsis are described. In addition, a monoalkylated l-piperideine, that is a new natural product, is described from a fifth Solenopsis species. Finally, the venoms of Monomorium latinode and M. subopacum are shown to contain an array of 2,5-dialkylpyrrolidines.

-

Jouvenaz, D. P., M. S. Blum, et al. (1972). "Antibacterial activity of venom alkaloids from the imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren." Antimicrobial Agents Chemotherapy 2: 291-293.

-

Leclercq, S., J. C. Braekman, et al. (1996). "Biosynthesis of the solenopsins, venom alkaloids of the fire ants." Naturwissenschaften 83: 222-225.

-

Leclercq, S., I. Thirionet, et al. (1994). "Absolute configuration of the solenopsins, venom alkaloids of the fire ants." Tetrahedron 50: 8465-8478.

-

Lind, N. K. (1982). "Mechanism of action of fire ant (Solenopsis) venoms. I. Lytic release of histamine from mast cells." Toxicon 20: 831-840.

-

MacConnell, J. G., M. S. Blum, Buren, W.F., Williams, R.N., Fales, H.M. (1976). "Fire ant venoms: chemotaxonomic correlations with alkaloidal compositions." Toxicon 14: 69-78.

-

MacConnell, J. G., M. S. Blum, et Fales, H.M. (1970). "Alkaloid from fire ant venom: Identification and synthesis." Science 168: 840-841.

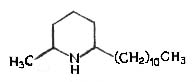

[Note: S. saevissima is S. invicta or S. richteri in North America] An alkaloid, trans-2-methyl-6-n-undecylpiperidine (solenopsin A), has been isolated from the venom of the fire ant Solenopsis saevissima. The structure has been confirmed by an unambiguous synthesis.

-

MacConnell, J. G., M. S. Blum, et Fales, H.M. (1971). "The chemistry of fire ant venom." Tetrahedron 26: 1129-1139.

[Note: S. saevissima is S. invicta or S. richteri in North America] Five alkaloids, three trans-2-methyl-6-alkylpiperidines, and two unsaturated analogues, have been identified in the venom of the red form of the fire ant, Solenopsis saevissima. The compounds are represented by the structural formulae I-V. Each has been prepared synthetically. These compounds, which appear to be the sole constituents of the venom, are believed unique among animal venoms.

-

Obin, M. S. and R. K. Vander Meer (1985). "Gaster flagging by fire ants (Solenopsis spp.): Functional significance of venom dispersal behavior." J. Chem. Ecol. 11: 1757-1768.

Behavioral and chemical studies with laboratory colonies indicate that the imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta Buren (Myrmicinae) disperses venom through the air by raising and vibrating its gaster (i.e., 'gaster flagging'). This mechanism of airborne venom dispersal is unreported for any ant species. Foraging workers utilize this air-dispersed venom (up to 500 ng) to repel heterospecifics encountered in the foraging arena, while brood tenders dispense smaller quantities (ca. 1 ng) to the brood surface, presumably as an antibiotic. Brood tenders removed from the brood cell and tested in heterospecific encounters in the foraging arena exhibited the complete repertoire of agonistic gaster flagging behavior. These observations suggest that airborne venom dispersal by workers is context specific rather than temporal caste specific and that workers can control the quantity of venom released.

-

Porter, S. D. (1992). "Frequency and distribution of polygyne fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Florida." Florida Entomol. 75: 248-257.

In order to determine the frequency and distribution of polygyne and monogyne fire ants (S. invicta) in Florida, preselected sites were surveyed from Key West to Tallahassee. Polygyne colonies were found at 15% of infested sites — a frequency similar to other states in the southeastern United States, but much less than in Texas. Polygyny was most common in the region around Marion county, but smaller populations were also scattered across the state. The density of mounds at polygyne sites was more than twice that at monogyne sites (262 versus 115 Mounds/ha), although mound diameters were about 20% smaller. Polygyne and monogyne queens averaged the same size (1.42 mm, head width), but monogyne queens were much heavier (24.3 mg versus 14.4 mg) due to their physogastry. As expected, workers in polygyne colonies were considerably smaller than those in monogyne colonies (0.28 mg versus 0.19 mg, dry fat-free).

-

Rhoades, R. B. (1977). Medical aspects of the imported fire ant. Gainesville, FL, University Presses of Florida.

[This book is divided into 5 chapters: The fascinating world of ants (21 p.), senses & communication (15 p.), venom (13 p.), clinical data (15 p.), and prevention and control (6 p.). There are 107 references, of which 30 are incorrect, incomplete, or duplicates.]

-

Schmidt, J. O. (1978). Ant venoms: study of venom diversity. Pesticide and venom neurotoxicity. D. L. Shankland, R. M. Holligworth and T. Smyth, Jr. New York, 283 p., Plenum Press: 247-263.

This chapter reviews the chemistry and toxinology of ant venoms; 68 references; new data on LD50 of Pogonomyrmex badius -- 0.42 mg/kg ip.

-

Schmidt, J. O. (1982). "Biochemistry of insect venoms." Annu. Rev. Entomol. 27: 339-368.

Comprehensive treatment of the venoms of insects including ants, wasps, bees, bugs (Heteroptera), Neuroptera, Diptera, and Coleoptera; 226 references. Headings and subheadings: Perspectives and overview; venom biochemistry; venoms used in prey capture; venoms of solitary parasitic and predatory wasps; orally derived venoms; venoms used as allomones, non-Hymenoptera; venoms used as allomones, Hymenoptera; macromolecules; peptides; micromolecules; non-protein constituents; insect venoms and phylogeny.

-

Schmidt, J. O. (1983). Hymenopteran envenomation. Urban Entomology: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. G. W. Frankie and C. S. Koehler. New York. 493 p., Praeger: 187-220.

Reviews the literature relating to insect stings and human reactions and fears of insects. Some new data on lethality of insect venoms to mice. Contents: Taxonomy of stinging insects, stinging behavior of Hymenoptera - general considerations, behavior and biology of stinging Hymenoptera, venoms - selection pressures and evolutionary considerations, venom biochemistry, threats to human health by stinging Hymenoptera, allergy to venom, the problem of cross-sensitivity, solutions to envenomation problems, the desensitization solution for hymenopteran envenomation - is it for everyone?, bridging the gap between entomologist and physician, conclusions, 5 pages of references.

-

Schmidt, J. O. (1986). Chemistry, pharmacology, and chemical ecology of ant venoms. Venoms of the Hymenoptera: Biochemical, pharmacological and behavioural aspects. T. Piek. London. xi + 570 p., Academic Press: 425-508.

Physiological, toxinological, chemical, and behavioral aspects of ant venoms reviewed. New primary data on LD50 of ant venoms, pain of stings, and enzymology of ant venoms presented. Contents headings: taxonomy, biological roles of venoms, offense, defense, chemical communication, ant venom collection and purification, venom biochemistry, non-proteinaceous venoms, proteinaceous venoms, physiological and pharmacological activities of venoms, paralysis and lethality against arthropods, paralysis and lethality against vertebrates, algogenicity, membrane activity, neurotoxicity, other activities, potential uses of venoms, ant venoms and people, ants: venom chemists and toxinologists par excellence, 11 pages of references. *[Dinoponera grandis (= gigantea), Odontomachus (= Stenomyrmex) emarginatus, Pachycondyla (= Neoponera) apicalis, Pachycondyla (= Termitopone) commutata, Pachycondyla (=Termitopone) laevigata, Pachycondyla (= Bothroponera) soror, ]

-

Schmidt, M., T. J. McConnell, et Hoffman, D.R. (1994). "Identification of nucleic acid sequence of two proteins from the fire ant venom, SOL i III and SOL i I." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 93: 223.

-

Schmidt, M., T. J. McConnell, et Hoffman, D.R. (1996). "Production of a recombinant imported fire ant venom allergen, Sol i 2, in native and immunoreactive form." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 98: 82-88.

-

Schmidt, M., R. B. Walker, Hoffman, D.R., McConnell, T.J. (1993). "Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding the imported fire ant venom allergen, Sol i II." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 91 (1 Part 2): 186.

-

Schmidt, M., R. B. Walker, et al. (1993). "Nucleotide sequence of cDNA encoding the fire ant venom protein Sol i II." FEBS Lett. 319: 13140.

-

Schwartz, H. J., D. L. Squillace, et al. (1986). "Studies in stinging insect hypersensitivity: Postmortem demonstration of antivenom IgE antibody in possible sting-related sudden death." Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 85: 607-610.

-

Sinski, J. T., G. A. Adrouny, et al. (1959). "Further characterization of hemolytic component of fire ant venom, mycological aspects." Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 102: 659-660.

-

Sonnet, P. E. (1967). "Fire ant venom: Synthesis of a reported component of solenamine." Science 156: 1759-1760.

-

Tomalski, M. D. (1981). Ant venom alkaloids: their repellent and debilitating effects on ant behavior, M.S. thesis, University of Georgia.

-

Stafford, C. T. (1992). "Fire ant allergy." Allergy Proc. 13: 11-16.

-

Stafford, C. T. (1996). "Hypersensitivity to fire ant venom." Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 77: 87-95.

-

Stafford, C. T., D. R. Hoffman, et al. (1989). "Allergy to imported fire ants." South. Med. J. 82: 1520-1527.

-

Stafford, C. T., L. S. Hutto, et al. (1989). "Imported fire ant as a health hazard." South. Med. J. 82: 1515-1519.

-

Stafford, C. T., L. S. Hutto, et al. (1989). "Survey of the imported fire ant as a health hazard." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 83: 231.

-

Stafford, C. T., J. E. Moffitt, et al. (1987). "Comparison of in vivo and in vitro tests in the diagnosis of imported fire ant (IFA) allergy." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 79: 233.

-

Stafford, C. T., J. E. Moffitt, et al. (1990). "Comparison of in vivo and in vitro tests in the diagnosis of imported fire ant sting allergy." Ann. Allergy 64: 368-372.

The specificities and sensitivities of skin test reactivity to imported fire ant (IFA) whole body extract (WBE) and IFA venom were compared with IFA WBE RAST and IFA venom RAST in the diagnosis of IFA allergy. Study groups consisted of 18 IFA allergic patients and 21 control subjects with no history of allergy to insect stings. All IFA allergic patients had positive skin tests to both IFA WBE and IFA venom. Six of 21 (29%) control subjects also had positive skin tests to both IFA WBE and IFA venom. A commercial IFA WBE RAST was positive in 10 of 18 (56%) IFA-allergic patients and 2 of 21 (10%) control subjects. Imported fire ant aqueous venom RAST was positive in 11 of 11 (100%) IFA-allergic patients and three of ten (30%) control subjects. Vespa IFA venom RAST was positive in 16 of 18 (89%) IFA-allergic patients and 5 of 21 (24%) controls. The sensitivities and specificities of IFA WBE skin testing, IFA venom skin testing, and IFA venom RAST did not differ significantly. Imported fire ant WBE RAST was less sensitive than the other diagnostic methods.

-

Stafford, C. T., R. B. Rhoades, et al. (1989). "Survey of whole body-extract immunotherapy for imported fire ant and other Hymenoptera-sting allergy." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 83: 1107-1111.

-

Stafford, C. T., R. B. Rhoades, et al. (1988). "Survey of immunotherapy for imported fire ant sting allergy." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 81: 203.

-

Stafford, C. T., S. L. Wise, et al. (1992). "Safety and efficacy of fire ant venom in the diagnosis of fire ant allergy." J. Aller. Clin. Immunol. 90: 653-661.

-

Storey, G. K. (1990). Chemical defenses of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta Buren, against infection by the fungus, Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuill., Ph.D. dissert., University of Florida, 76 p.

[Dissert. Abstr. Int. B 51: 4687-4688] [Order # 9106479]

-

Tschinkel, W. R. (1988). "Colony growth and the ontogeny of worker polymorphism in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta." Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 22: 103-115.

Colony size and worker polymorphism (headwidth) were determined for fire ant colonies ranging from incipient to 12 year of age. Colonies grew approximately logistically, reaching half size between 2 1/2 and 3 1/2 yr and reaching their maximum size of about 220 000 workers after 4 to 6 yr. Colony size showed strong seasonal variation. There was some evidence that growth rate may vary with food density. Incipient colonies are monomorphic and consist of small workers only, but as colonies grow, production of larger workers causes the size-frequency distributions to become strongly skewed. These skewed distributions were shown to consist of two slightly overlapping normal distributions, a narrow one defined as the minor workers, and a much broader one defined as the major workers. Major workers differ from minor workers in having been subjected to a discrete, additional stimulation of body growth resulting in a second normal subpopulation. The category of 'media' is seen to be developmentally undefined. The mean headwidth of the workers in both these subpopulations increased during the first 6 mo. of colony life, until the colonies averaged about 4000 workers. Headwidth of minors declined somewhat in colonies older than about 5 yr, but that of majors remained stable. When the first majors appear, their weights average about twice that of minors. This increase of about 4 times at 6 mo. and remains stable thereafter. The range of weights of majors is up to 20 times that of minors. Growth of the subpopulation of major workers is also logistic, but more rapid than the colony as a whole, causing the proportion of major workers to increase with colony size. In full sized colonies, about 35% of the workers are majors. Total biomass investment in majors increases as long as colnies grow, beginning at about 10% at 2 months and reaching about 70% in mature colonies. This suggests that major workers play an important role in colony success. The total dry biomass of workers peaked at about 106 g, that of majors at about 72 g. These values then fluctuate seasonally in parallel to number of workers. When colony growth ceases, the proportion of majors remain approximately stable. Colony size explained 98% in the variation of the number of major workers.

-

Tschinkel, W. R. (1988). "Distribution of the fire ants Solenopsis invicta and S. geminata (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in northern Florida in relation to habitat and disturbance." Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 81: 76-81.

The occurrence of Solenopsis invicta Buren and S. geminata (F.) is almost nonoverlapping in certain natural ecotypes in north Florida In the high, deep-sand pinelands with a deep water table, S. invicta is entirely limited to margins of seasonal ponds and heavily disturbed sites such as pastures or margins of paved or frequently graded roads. S. geminata is common throughout the longleaf pine forest, both in mature stands and clearcut replanted areas, but it is nearly absent from heavily disturbed or pond-side sites occupied by S. invicta. Solenopsis geminata is rare throughout flatwoods sites where the water table is close to the surface and S. invicta is a common colonizer of clearcut replanted areas and of graded roadsides. S. invicta also occurs at low densities in mature flatwoods, mostly along ungraded roads. This distribution is discussed in relation to biotic and abiotic factors.

-

Tschinkel, W. R. and D. F. Howard (1980). "A simple, non-toxic home remedy against fire ants." J. Georgia Entomol. Soc. 15: 102-105.

Three gallons of hot water (about 90 C) poured slowly on each of 14 fire ant mounds produced excellent to complete kill in 8 of 14 cases, moderate kill in 3/14, poor kill in 2/14 and no kill in one. Colonies similarly treated with three gallons of cold water were normal. We therefore suggest the use of hot water as a simple, humble but effective treatment against fire ants around the home. Its advantages are instantaneous effect, ease of application and absence of residual toxicants.

-

Tschinkel, W. R. and D. F. Howard (1983). "Colony founding by pleometrosis in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta." Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 12: 103-113.

-

Tschinkel, W. R., A. S. Mikheyev, et Storz S.R. (2003). "Allometry of workers of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta." J. Insect Sci. 3:2: 11 p.

-

Tschinkel, W. R. and S. D. Porter (1988). "Efficiency of sperm use in queens of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 81: 777-781.

Like most social Hymenoptera, queens of the fire ant, S. invicta Buren, mate only at the beginning of their reproductive lives. They receive an initial supply of about 7 million sperm which they gradually parcel out over a period of almost 7 yr until the supply is exhausted and they can no longer produce female offspring. Using the monogynous form of the fire ant, efficiency of sperm use was determined directly by allowing four newly mated queens to rear approximately 0.5 million workers. The mean sperm count of these queens declined by 1.7 million from the starting value, yielding an efficiency of 3.2 sperm per adult female offspring. Sperm-use efficiency was also determined indirectly for field queens based on calculations that show these queens expend 7.0 million sperm to produce 2.6 million workers for an efficiency of about 2.6 sperm per adult female. Lifetime worker production was calculated from annual estimates of colony growth and worker turnover. These estimates of fire ant sperm-use efficiency are about 10 times higher than those reported for honey bee queens and astronomically higher than those of most nonsocial animals. Apparently, efficient use of sperm is an important reproductive capability for S. invicta and other social insects with high reproductive outputs.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. (1983). "Semiochemicals and the red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta Buren) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." Florida Entomol. 66: 139-161.

The trail pheromone has received by far the most attention over the years, and this has resulted in many excellent behavioral studies. The recent structure elucidation of several trail pheromone components has opened up the possibility of fully understanding this chemically and behaviorally complex pheromone system. It is very interesting that both recruitment and trail following are released by different pheromone components produced in the Dufour's gland. A more detailed look at these behaviors versus trail chemistry may reveal even more intriguing relationships. Interest in queen pheromones, in all of their aspects, has experienced a resurgence of activity since the initial discovery of their existence in 1974. Of particular importance was the development of specific bioassays to measure attraction and queen recognition, and the discovery of the venom sac and gland as the source of these pheromones. The venom of queen and worker will surely come to be classic examples of glandular and pheromonal parsimony. The primer pheromone that inhibits the dealation of alates is a behaviorally unique system. Certainly one of the major goals in queen pheromone research is the identification and isolation of pheromone components. There has been no published work on the brood pheromone since 1975, perhaps because that paper claimed to have identified the pheromone as a triglyceride. However, I do not see any bona fide evidence for that claim and consider the brood pheromone as a problem waiting to be solved.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. (1986). Chemical taxonomy as a tool for separating Solenopsis spp. Fire ants and leaf cutting ants: biology and management. C. S. Lofgren and R. K. Vander Meer. Boulder. xv + 435 p., Westview Press: 316-326.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. (1986). The fire ant sting apparatus: a case of harmonious parsimony, Abstr. 10th Inter. Congr. IUSSI, p. 141.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. (1987). The fire ant sting apparatus: A case of harmonious parsimony. Chemistry and biology of social insects. J. Eder and H. Rembold. Mьnchen. 757 p., Verlag J. Peperny: 449-450.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. (1988). Behavioral and biochemical variation in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Interindividual behavioral variability in social insects. R. L. Jeanne. Boulder, CO. 456 p., Westview Press: 223-255.

Fire ants, especially Solenopsis invicta, have been studied intensively for the past thirty-five years. Variability in behavior and biochemistry has been detected at every stage of colony development. Nanitic workers, the first adults produced by colony founding queens, differ behaviorally and chemically from their mature colony counterparts. As a colony matures the worker size distribution changes and certain behavior patterns are preferentially performed by specific size categories. In addition, workers undergo age related polyethism, moving from nurse to forager as they become older. Venom alkaloids (2-alkyl or alkenyl 6-methyl piperidines) vary both qualitatively and quantitatively with the size of the worker, but there are no differences between temporal castes of the same size. Adult workers require the venom alkaloids regardless of their function; nurses use it to disinfect the brood and nest, while foraging workers use it to secure prey and defend the colony. The responsiveness of workers to pheromone systems in general diminishes with the physiological age of the individual. Also, the behavioral responsiveness of colonies often shows considerable variation, for example in initial trail formation. Female sexuals are very complicated in terms of their sexual maturity and the events, both behavioral and biochemical, that take place after mating. Nestmate recognition factors, as modeled by the cuticular hydrocarbons, have been shown to be statistically different from colony to colony and in a dynamic state of flux. In conjunction with evidence for continuous mixing of colony odor, these data suggest that individual workers continually update their perception of colony odor and, therefore, nestmate recognition cues.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. (1988). Physiology and behavior of the imported fire ant. The imported fire ant: Assessment and recommendations. S. B. Vinson and J. Teer. Austin, TX, Proc. Governor's Conf., Sportsmen Conservationists of Texas: 18-23.

-

Vander Meer, R. K., B. M. Glancey, et al. (1980). "The poison sac of red imported fire ant queens: Source of a pheromone attractant." Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 73: 609-612.

The poison sac of queens of the imported fire ant, S. invicta Buren, has been identified as the novel storage site of a queen pheromone. The pheromone elicits orientation and attraction in workers and promotes the deposition of brood. Alkaloids normally associated with the venom of imported fire ants are not responsible for the behavior produced by the queen pheromone.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. and C. S. Lofgren (1988). "Use of chemical characters in defining populations of fire ants (Solenopsis saevissima complex) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)." Florida Entomol. 71: 323-332.

The fire ants, Solenopsis invicta and S. richteri, were accidentally imported into the United States in the first half of this century from South America. In their adopted habitat the imported fire ants have thrived causing considerable medical and agricultural problems in the nine widely infested states of the south and southeast. The red imported fire ant, S. invicta was considered the dominant ant in the infested areas, having displaced the black imported fire ant, S. richteri, into a small enclave in northeastern Mississippi. However, a large reproductively viable S. invicta/S. richteri hybrid population was recently discovered across northern Alabama and into Mississippi and Georia by chemical analysis. This paper reports on the use of three species-specific chemical characters (venom alkaloids, cuticular hydrocarbons, and trail pheromones) to define S. invicta, S. richteri, and hybrid populations in the United States. In addition, these characters have been applied to fire ant taxonomy in South America. We also discuss fire ant population dynamics in the United States and its implications on several models of hybridization. These results have important consequences regarding the species status of the two imported fire ants and the taxonomy of fire ant populations in South America.

-

Vander Meer, R. K., C. S. Lofgren, et al. (1985). "Biochemical evidence for hybridization in fire ants." Florida Entomol. 68: 501-506.

-

Vander Meer, R. K., E. Merdinger, et al. (1981). "Recent biochemical studies of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta." Farmacia 29: 145-152.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. (1993). Reflections of a chemist on ant social behavior, Abstr. 14th Meeting Deutsch. sektion IUSSI, p. 14-15.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. and C. S. Lofgren (1990). Chemotaxonomy applied to fire ant systematics in the United States and South America. Applied myrmecology: a world perspective. R. K. Vander Meer, K. Jaffe and A. Cedeno. Boulder. xv + 741 p., Westview Press: 75-84.

-

Vander Meer, R. K. and L. Morel (1995). "Ant queens deposit pheromones and antimicrobial agents on eggs." Naturwissenschaften 82: 93-95.

*[Oviposition behavior described for S. invicta was observed in M. pharaonis.]

-

Vander Meer, R. K., T. J. Slowik, et al. (2002). "Semiochemicals released by electrically stimulated red imported fire ants, Solenopsis invicta." J. Chem. Ecol. 28: 2585-2600.

The red imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta Buren, has evolved sophisticated chemical communication systems that regulate the activities of the colony. Among these are recruitment pheromones that effectively attract and stimulate workers to follow a trail to food or alternative nesting sites. Alarm pheromones alert, activate, and attract workers to intruders or other disturbances. The attraction and accumulation of fire ant workers in electrical equipment may be explained by their release of pheromones that draw additional worker ants into the electrical contacts. We used chemical analysis and behavioral bioassays to investigate if semiochemicals were released by electrically shocked fire ants. Workers were subjected to a 120 V, alternating-current power source. In all cases, electrically stimulated workers released venom alkaloids as revealed by gas chromatography. We also demonstrated the release of alarm pheromones and recruitment pheromones that elicited attraction and orientation. Arrestant behavior was observed with the workers not electrically stimulated but near those that were, indicating release of unknown behavior- modifying substances from the electrically stimulated ants. It appears that fire ants respond to electrical stimulus by generally releasing exocrine gland products. The behaviors associated with these products support the hypothesis that the accumulation of fire ants in electrical equipment is the result of a foraging worker finding and closing electrical contacts, then releasing exocrine gland products that attract other workers to the site, who in turn are electrically stimulated.

-

Vander Meer, R. K., D. P. Wojcik, et al. (1988). Chemical differentiation of cryptic fire ant species?, Proc. 5th annual Meeting of the International Society of Chemical Ecology, p. 55.

-

Vinson, S. B. (1980). "The physiology of the imported fire ant." Proc. Tall Timbers Conf. Ecol. Anim. Control Habitat Manage. 7: 67-85.

-

Vinson, S. B. (1988). preface for the recommendations for research and education. The imported fire ant: Assessment and recommendations. S. B. Vinson and J. Teer. Austin, TX, Proc. Governor's Conf., Sportsmen Conservationists of Texas: 107-109.

-

Vinson, S. B. (1990). Fire ants in the urban environment, Proceedings of the 1990 National Conference on Urban Entomology, p. 77-87.

-

Vinson, S. B. (1991). "Effect of the red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) on a small plant-decomposing arthropod community." Environ. Entomol. 20: 98-103.

Rotting fruit exposed to the red imported fire ant, S. invicta Buren, was consumed by the ants, which successfully prevented colonization by other decomposer arthropods. When fire ants were excluded, the fruit was colonized by large numbers of several species of Diptera (Drosophilidae and Tephritidae) and Coleoptera (Nitidulidae and Staphylinidae), as well as small numbers of parasitic Hymenoptera and other arthropods. When rotting fruit was colonized by these decomposer arthropods and then exposed to Solenopsis inuicta, the remaining fruit and the fruit colonizers were consumed by the ants. The data demonstrate that fire ants rapidly locate and recruit to rotting fruit where they consume other decomposer arthropods, exclude invasion by other decomposer arthropods, and use the decomposing resource themselves.

-

Vinson, S. B. (1997). "Invasion of the red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): Spread, biology, and impact." Am. Entomol. 43(1): 23-39.

-

Vinson, S. B. and S. Ellison (1996). "An unusual case of polygyny in Solenopsis invicta Buren." Southwest. Entomol. 21(4): 387-393.

*[Physogastric queen were found in polygynous colonies.]

-

Vinson, S. B. and L. Greenberg (1986). The biology, physiology, and ecology of imported fire ants. Economic impact and control of social insects. S. B. Vinson. New York. 421 p., Praeger: 193-226.

-

Vinson, S. B. and T. A. Scarborough (1991). "Interactions between Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), Rhopalosiphum maidis (Homoptera: Aphididae), and the parasitoid Lysiphlebus testaceipes Cresson (Hymenoptera: Aphidiidae)." Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 84: 158-164.

*[RIFA reduced emergence of the aphid parasite. RIFA detected parasitized aphids after 6 days and removed them for food. Ants moved starved aphid to new plants.]

-

Wojcik, D. P. (1986). "Bibliography of imported fire ants and their control: Second Supplement." Florida Entomol. 69: 394-415.

Обзор литературы до октября 1985

смотрите www.fcla.edu/FlaEnt >>>

-

Wojcik, D. P. (1989). "Behavioral interactions between ants and their parasites." Florida Entomol. 72: 43-51.

Экто- и эндопаразитические членистоногие у муравьев: Acarina (Antennophoridae, Macrochelidae, Uropodidae), Strepsiptera, Myrmecolacidae, Hymenoptera (Diapriidae, Eucharitidae, Formicidae), and Diptera (Phoridae). Variation in the style of ectoparasitism is illustrated by the different lifestages involved and differing effects on the hosts by parasitic ants and eucharitids. Considerable variation in behavior occurs between related genera and species of phorids emphasizing the danger of over-generalization on the relationships of ants and their parasites.

|